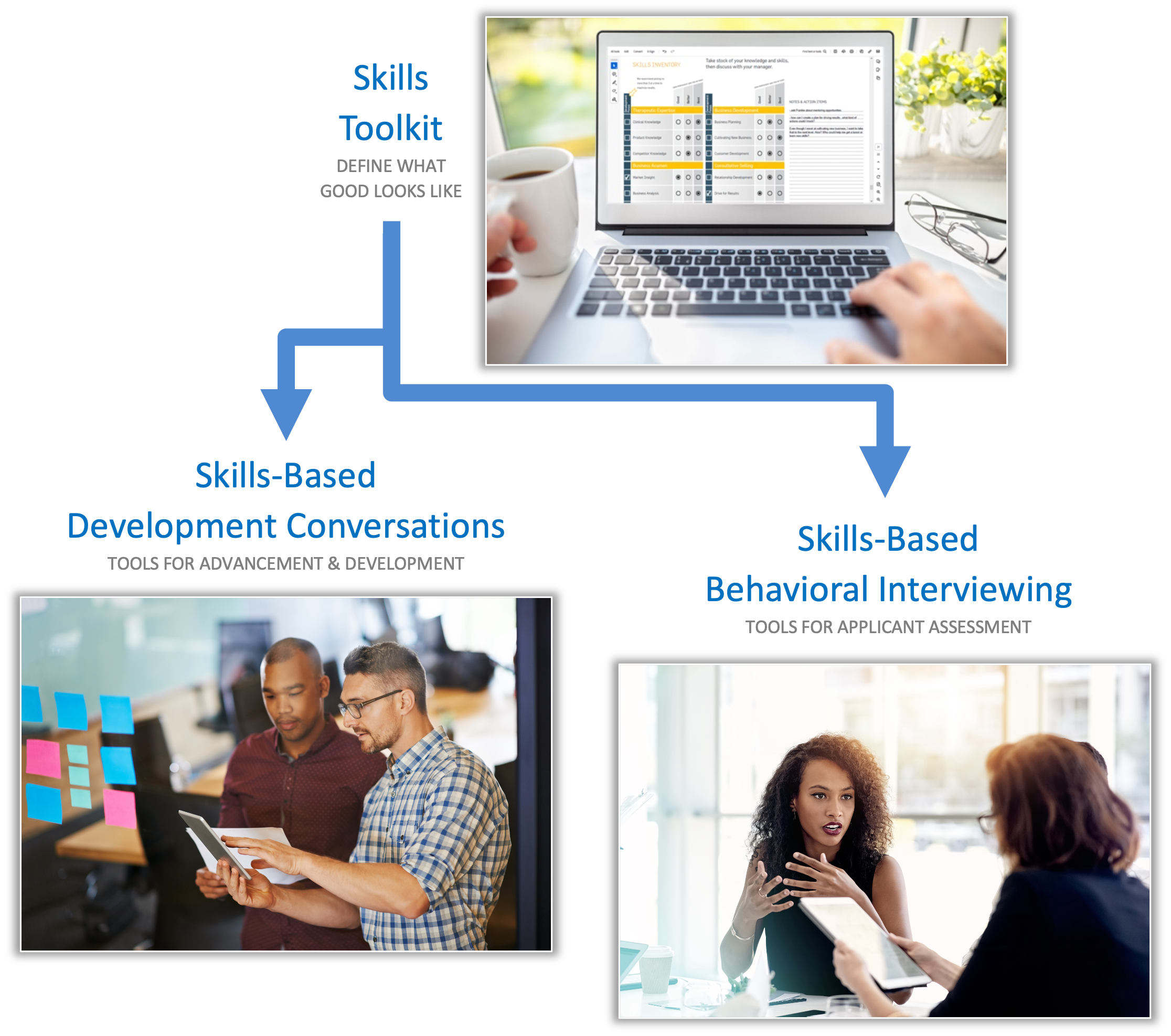

In this case study, I’ll share with you an approach that we use to support managers in shifting their conversations with employees to skill building.

The Challenges

Here on the front lines of the talent war, we know the value of ongoing skill development, but it can be difficult to get people leaders to focus the necessary time and effort on growing their team members’ capabilities. Taking time away from day-to-day operational issues and fire fighting is tough enough, but even when managers are willing to engage in development conversations, they often lack the tools and know-how to get started. Previous attempts to offer career development have been hampered by three factors:

#1: Manager Bandwidth

According to Gartner research described in a recent HBR article (Basu, Das et.al, 2024), “managers today are accountable for 51% more responsibilities than they can effectively manage…. As a result, 54% of managers are suffering from work-induced stress and fatigue, and 44% are struggling to provide personalized support to their direct reports.” Managers are caught between the ever-growing expectations of their leaders and the ever-widening needs of their colleagues and subordinates. Beyond the day-to-day firefighting, there is little room for employee-manager interaction.

#2: Unclear Expectations

Employees want to know “what does it REALLY take to get ahead here?” So much is expected of them; what’s MOST important? The answers help employees focus on the bigger picture and know where to invest their development efforts. Unfortunately, when they turn to their leaders, they often get mixed, ambiguous messages, which can be summed up as, “Just keep doing what you’re doing and good things will come,” as one manager recently shared with us. Employees and managers need to have a common framework of expectations for what career advancement looks like and what it will take to achieve it. Otherwise, everyone is just stuck in a rut.

#3: Capability Gap

Unless our client’s managers learned coaching skills from a previous employer, these managers lacked training and support, and even the confidence, to initiate conversations about HOW to be more effective. With a start-up mentality, these managers have been conditioned to focus on driving performance results at the exclusion of all other success factors, even if they know that HOW results are achieved are just as important—if not more so—than WHAT results are achieved. The HOW relates to doing things the right way, in alignment with company values and priorities.

The Solution Architecture

Part 1: Boot Camp

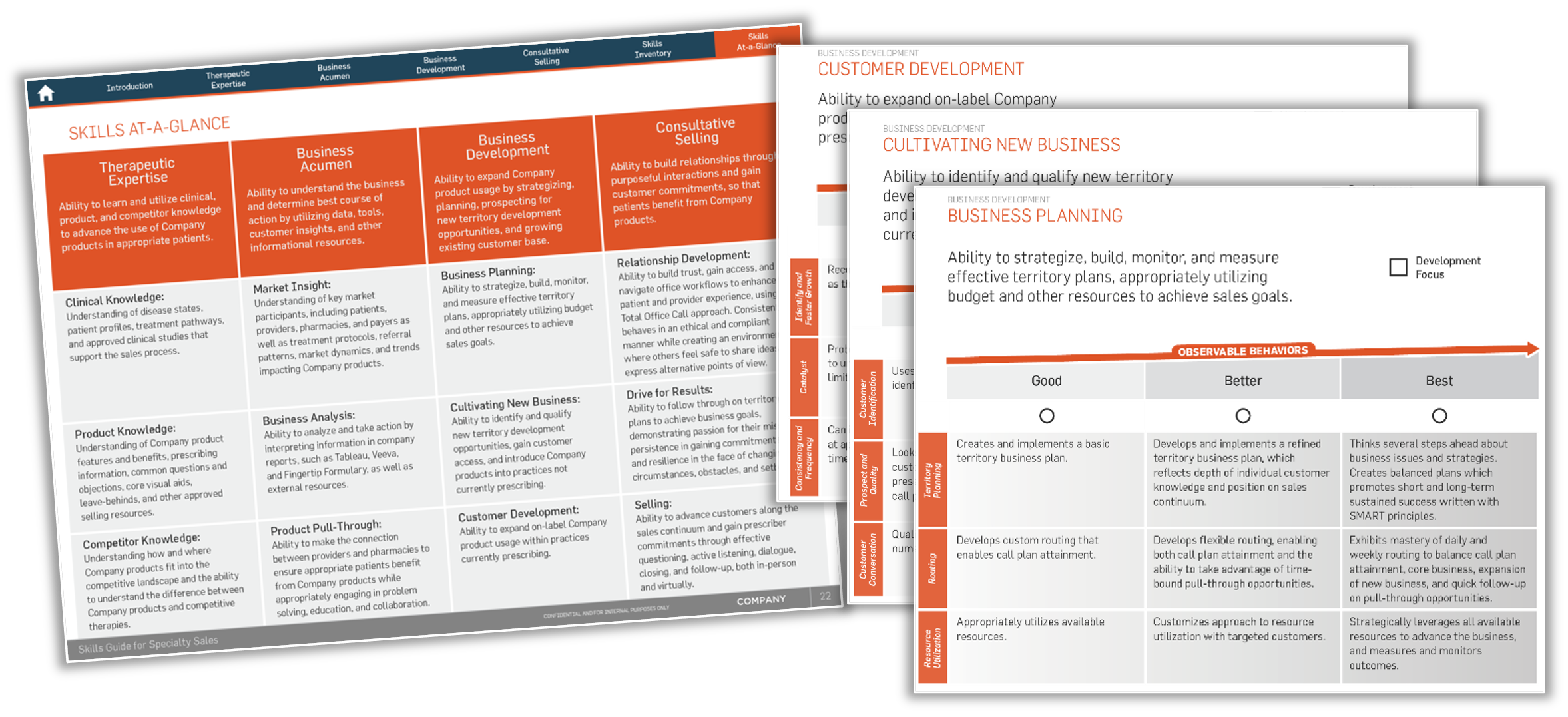

To focus development conversations on what is most critical, we began by developing a model of key skills mapped to the role and to good-better-best behaviors.

Skills Mapping: Our journey started with skills mapping, where we identified the skills required to succeed in each role and prioritized the key skills that truly differentiated successful employees. We started by reviewing documentation (e.g., job descriptions) and using ChatGPT to pick out skills, activities, processes, and tasks related to the job. In this case, we also conducted interviews with top and average performers and their leaders. From these inputs, we created a “strawman” list of skills, which we then vetted through an advisory group to derive a prioritized list of the key skills. At the client’s request, these skills were categorized under competency domains to make them easier to work with and roll up.

Behavior Mapping: With some projects, clients are satisfied with just mapping the key skills—and that indeed can take you a long way—but in this case, we were asked to elaborate on each skill, describing what good, better, and best behaviors look like. For example, with closing skills, what would the minimum expectation be in terms of a salesperson demonstrating closing skills (good), what would it look like when a salesperson is fully capable at closing skills and able to do it fluidly (better), and what would an expert look like when closing (best) under the most difficult conditions? Again, we drafted a “strawman” set of behavior criteria for our advisory group to vet.

Skills Mapping (left) and Behavior Mapping (right) examples

Part 2: Skills-Based Development Conversations

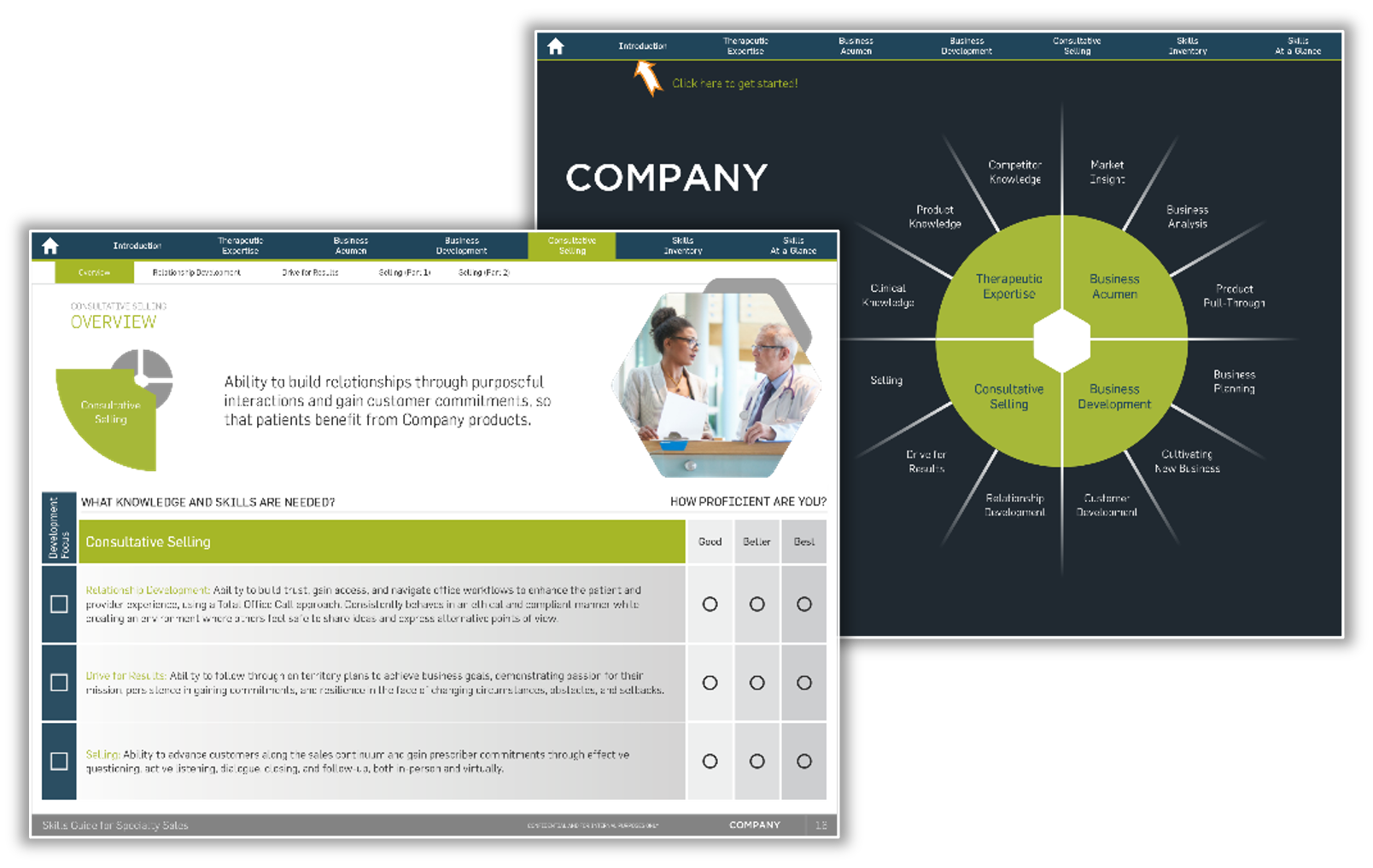

Next, we needed a suite of tools to support those critical discussions around skills-building. This involved a two-pronged approach, creating a robust Skills Guide with curated resources and developing Career Ladders to offer recognized avenues of advancement based on performance and skill.

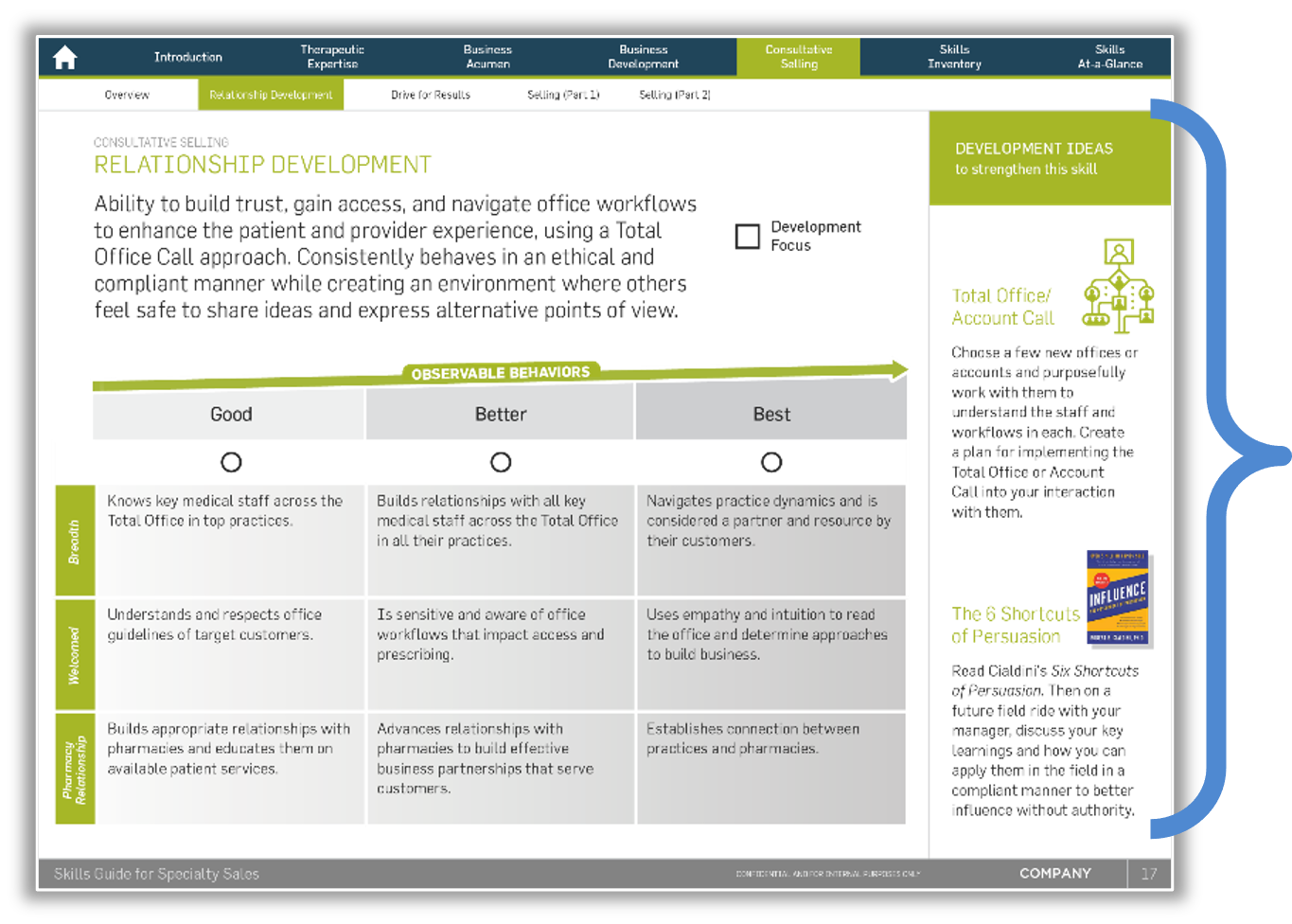

Skills Guide: The interactive PDF called the Skills Guide described the skills, recommended curated resources for each skill, and defined each skill’s behavioral criteria.

The Skills Guide

Curated Resources: Once an individual identifies where they are on a behavioral continuum, and they decide that they want to move from good to better or better to best, where can they turn to for help in developing that skill? Here again, we went beyond skills mapping by recommending educational resources, tools, and activities for each key skill. In the Skills Guide, employees and managers found links to the resources displayed next to each skill description.

Curated Resources for skill development

Career Ladders: Skills maps alone can be very helpful in fueling development conversations, but career ladders can turbo-charge those interactions by providing a strong incentive for both employees and managers. Career ladders are recognized avenues of advancement, basically a series of levels employees can climb within their current role based on performance, skill, and other criteria set by the leadership team. This creates a carrot where employees focus their development efforts on the right things, and it gives their manager a natural way to inject professional development into the conversation. It goes like this…

Career Ladder & Path Mapping

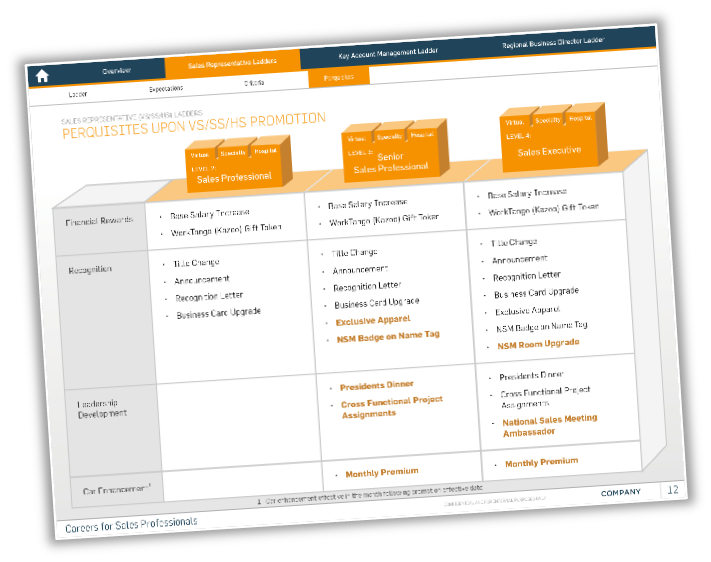

What Does a Ladder Include?

When you establish career ladders for different roles and role families, you create a career ecosystem where employees can see a future for themselves and explore different possible career paths through your organization.

- Expectations: As an employee climbs each rung of the ladder, expectations should grow, in terms of their performance results, their behavior, their role on the team, and their investment in their professional development.

- Criteria: Each ladder should describe how the individual can satisfy criteria to qualify for consideration at the next level. We also describe the individual’s development journey, what skills they need to master—and to what extent—as they rise to meet the growing expectations.

- Perks: Ladders define the perquisites they receive for reaching a new level within their career ladder. These can include monetary rewards (salary increase, bonus, reward tokens), recognition (e.g., title change), development opportunities, and other incentives.

Career Ladder Perks Guide

Part 3: Skills-Based Behavioral Interviewing

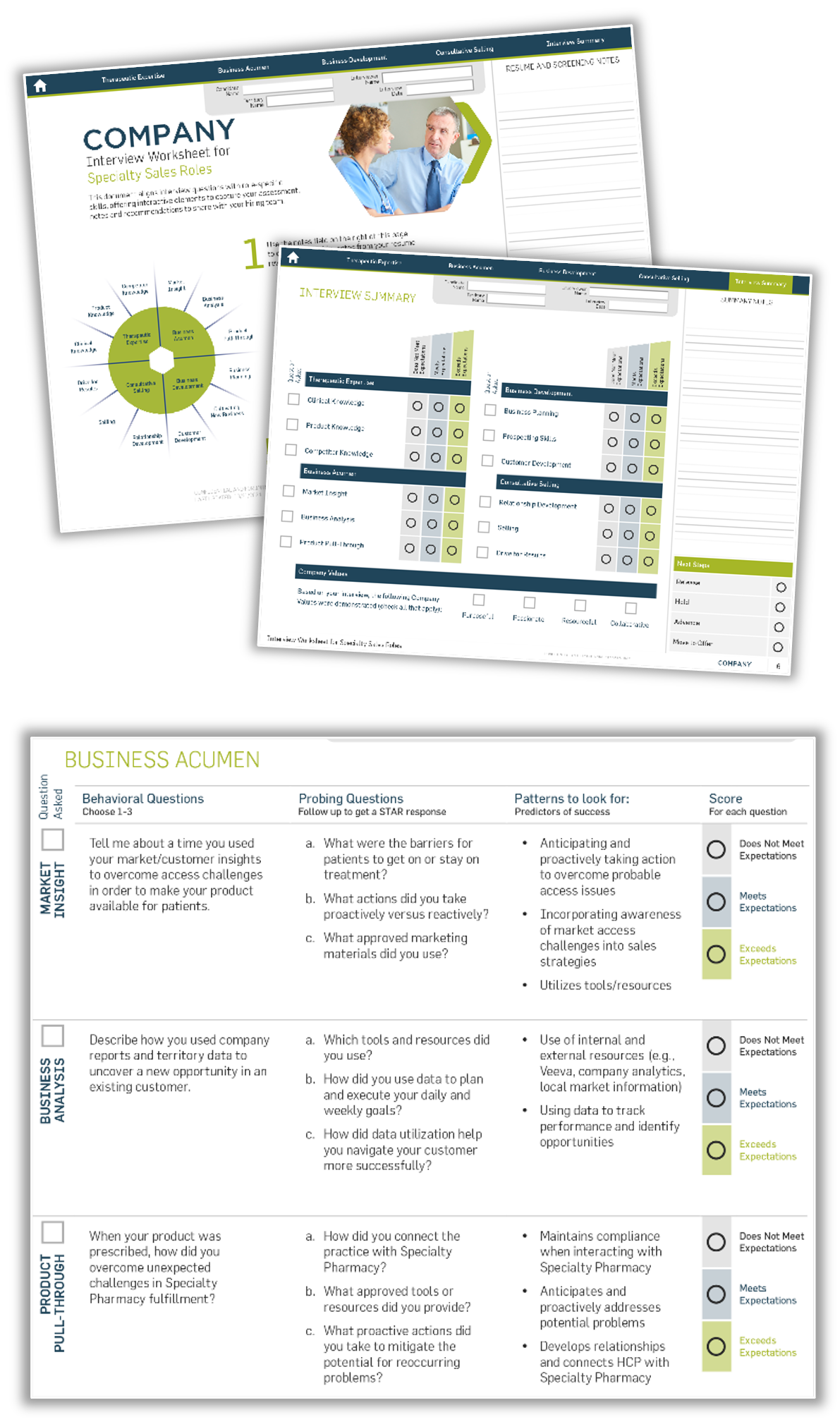

How do we ensure that we are hiring the right applicants? With skills & behavior mapping, we can bake those assessments into the talent acquisition process by creating templates that guide interviewers in asking skill-based questions during behavioral interviews with criteria for evaluating responses.

Interview Worksheet: Hiring managers often ask, “Tell me about yourself.” Unfortunately, the answers don’t really inform the interviewing process all that much.

A better approach is to get hiring managers to uncover what candidates’ work experiences reveal about their skill level. Hiring managers can do this by asking behavioral interviewing questions that focus on the candidate’s work experiences. Often these questions start with, “Tell me about a time when you….”

So, we developed an interactive PDF for interviewing that contains behavioral interviewing questions mapped to the role’s key skills.

- Behavioral Questions: Interviewers select a few key skills in advance. The hiring manager may choose to assign certain interviewers to explore certain skills.

- Probing Questions: The worksheet also suggests probing questions for interviewers to dig deeper and uncover insights into the candidate’s capabilities.

- Patterns to Look For: The worksheet describes behavioral criteria that the interviewer should be attentive to in the responses and should use when rating the candidate on that skill.

- Score: The worksheet provides a way for the interviewers to score each candidate in terms of how well they meet skill expectations, plus space for interviewers to take notes.

Skills-Based Interview Worksheets

“In my 20 years in the industry, I’ve never seen anything this professional and easy to use. Instead of avoiding the subject, I feel empowered to initiate conversations that will grow my team’s capabilities.”

Design Principles at Work

This case study illustrates the real-world application of four performance-based instructional design principles:

- Target Audience Inclusion: From day one, we requested input from a select group of employees and managers, a subset of which formed our advisory group, who had final say on all design and content decisions. That level of participation was critical in getting the skills, career ladders, curated resources, and interviewing worksheet right. More importantly, by getting stakeholder involvement early and often, we ensured the audience would be receptive when the program rolled out to the field.

- Granular Yet Simple: High-level competencies (e.g., Business Acumen, Selling Skills) encompass a wide array of knowledge, skills, and abilities, which can make them too big and too broad to be useful for assessment and coaching purposes. To give employees and managers something useful, we got down to individual skills that were used all the time by the target audience. The challenge with skills, however, is that they can quickly multiply out of control, so to keep the skills map simple enough for day-to-day use, we prioritized the skills that truly differentiated the most capable team members. Keeping the list down to the top 15-25 skills seems to be about right.

- Observable Behaviors: For any talent management or talent development efforts to succeed, employees and managers need a shared understanding of what good looks like. For that reason, we worked with our advisory group to define precisely the observable behaviors associated with each key skill, and how those behaviors improve as someone progresses from beginner to intermediate to advanced; in other words, from good to great. While painstaking, aligning the stakeholders with a common understanding of these behavioral criteria ensured that managers would have what they needed to engage in development conversations.

- What’s In It For Me? In today’s demanding and fast-paced workplace, it’s a lot to expect employees to engage actively in their development on their own time, at their own expense, and with no incentives. Their development outside of work might include graduate school, certifications, and other experiences that will help them land a future role. But if you want them to invest actively in getting better at their CURRENT job, there needs to be some incentive, especially if that improvement greatly contributes to business results. With this case, the career ladder rewards provided the carrot and answered the WIIFM question, propelling team members forward to ask themselves and their managers, “What must I do to advance to the next level in my career?”

This case study demonstrates how a few intelligently designed tools can serve as a catalyst for establishing a learning organization, where employees actively engage in their professional growth and their managers are encouraged to support the growth of their team’s capabilities.

We welcome your perspective on other ways to make workplace training more effective and impactful. Drop us a line!