With a new CEO at the helm, this global manufacturer of industrial lighting had set off in a new direction with a bold strategy. But how well would that strategy materialize if the company continued to work in the same old ways? The CEO reminded leadership, “culture eats strategy for breakfast,” an adage often attributed to Peter Drucker. He emphasized to the leadership team that regardless of how well thought-out their business strategy was, the company’s culture—its way of doing things—would determine how successfully the strategy could be executed.

With that in mind, they embarked on a multi-pronged initiative for cultural transformation, and my team had the privilege of supporting them in every aspect of it. In this case study, I’ll share our solution architecture and how we operationalized each element to accelerate the desired cultural changes.

The Challenges

After a shake-up in the board of directors and leadership team, our client sought to bring about a cultural transformation that would support its new vision, mission, and business strategy.

As a well-established player in the industrial lighting industry, the business’s culture was highly entrenched and engineering-centric. The new leadership team wanted to shift that culture to be more innovation-centric, with the organizational agility needed to bring new client-centered solutions to market quickly. Organizational agility isn’t just a product of policies, org charts, processes, and tools…it has as much to do with people sharing an innovation mindset, collaborating well across boundaries, and valuing and respecting others’ ideas and contributions.

There were several challenges to overcome.

#1: Competition Over Collaboration

The business was organized into separate and distinct product lines, departments, and sites with little-to-no communication happening across these silos and no incentives to collaborate. In fact, the previous leadership team encouraged internal competition as a way to bring out the best performance from each siloed group. In this culture, engineers kept ideas and progress close to the vest.

For innovation, they needed to foster the opposite: collaboration, trust, and idea sharing.

#2: Small World, Small Thinking

Although the company had a global footprint, with customers and sales offices all over the world and manufacturing plants in LATAM and APAC, there was remarkably little interaction between US-based executives and engineers and the broader international community. They were very much an analog culture, where in-person interaction was the primary means of communicating. As a result, their world was small, focused mainly on the people they could see and interact with at their offices and nearby customer sites.

Innovation requires understanding customer perspectives, respecting divergent viewpoints, and exhibiting an openness to new ideas…they would need to expand their horizons.

#3: Exclusion Rather Than Inclusion

In this highly competitive, analog culture, it was difficult to attract and retain bright new team members who could bring new thinking and ways of doing things. Decision-making was top-down and input was not widely sought out, leaving many feeling locked out of the discussion.

Creative minds felt stifled. Some groups were made to feel as if they did not belong. Divergent voices were ignored or minimized. The most innovative minds were leaving the company, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to replace them.

The Solution Architecture

Part 1: Skills Framework

Like many organizational change projects, this one began with the question: “What does the desired future state look like?” We posed this question to the CEO and his executive team during several brainstorming sessions. We also asked, “To bring about this new way of working, and this new culture that you want to foster, what behaviors and skills do you want to see improve across the organization?

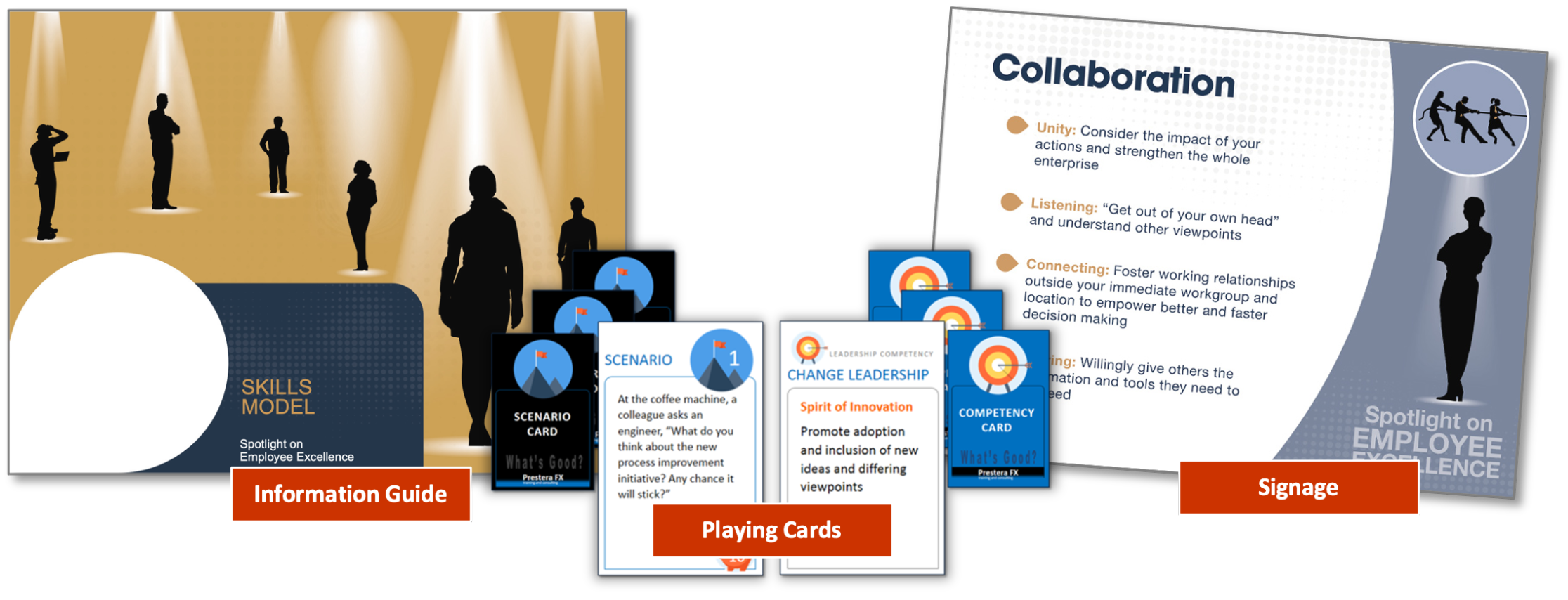

Information Guide: Using input from interviews, brainstorming workshops, and engagement survey results, we built a strawman framework that defined the Core Competencies, Skills, and Behaviors needed to support the cultural change that the leadership team wanted to bring about across the company.

We debated, word-smithed, and iterated the framework into a final state, then created an Information Guide to communicate the new mindset and the skills needed to achieve the desired end state. We expected all employees to develop and demonstrate these “core skills” each day, regardless of their job function, seniority, or job level. Each skill was defined in terms of observable behaviors, which was vital to helping people understand the framework and how to evaluate themselves and others against it.

The framework was embedded into interviewing guides, onboarding, performance appraisals, and other talent management processes.

Skills Framework Information Guide (left) and Communications Campaign Assets (right and center)

Communications Campaign: Once we established the framework, we started building training and communication assets to support the change initiative.

We developed a set of posters, for example, translating the skills and localizing the behaviors for employees based in different countries. At a manufacturing site, you would find these posters displayed on the wall directly in front of the production line, so that operators would see them every day. Flyers, digital signage, playing cards, email blasts, and other communication assets were likewise branded, localized, and deployed to all sites.

The comms plan also included town hall meetings hosted at different sites each time, so that the leadership team could engage directly with employees globally.

Part 2: Skills-Based Training and Curated Resources

We attacked skill development from three sides: (1) we created an on-demand, skills-mapped curriculum of video-based elearning modules; (2) we created a series of resource lists, containing links to curated resources for each skill; and (3) we created team development resources to support managers in conducting one-on-one and team development conversations with their people.

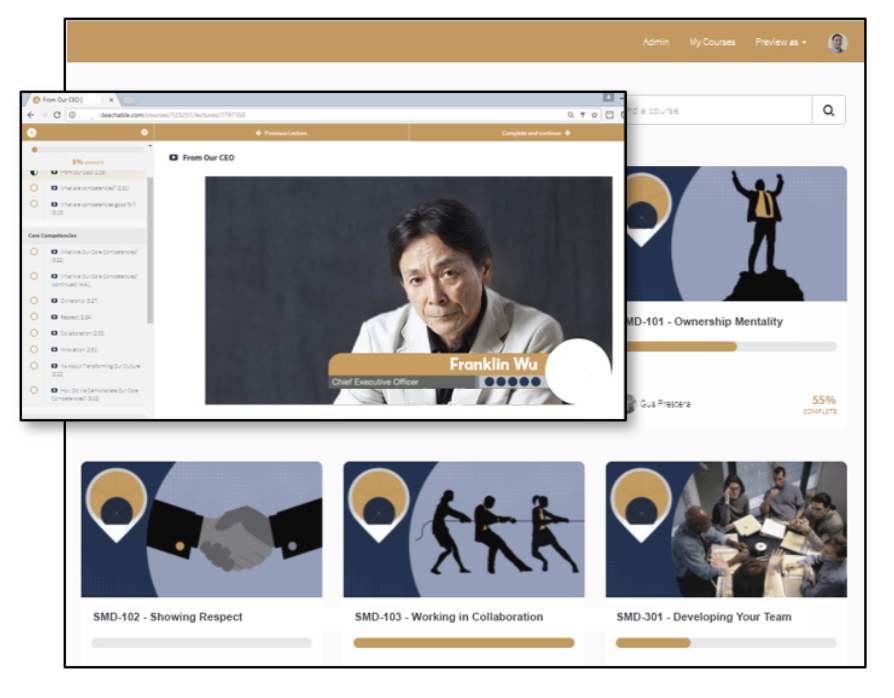

Skills-Mapped Curriculum: We filmed interviews with the CEO and other senior leaders, then organized the footage into a series of elearning modules, each mapping back to a specific skill in the framework. Through these elearning modules, business leaders could speak directly to their people about what the new skill meant to them. They gave examples to depict what good and bad looked like and spoke to why those behaviors were important to the success of the business. These leader videos were combined with more traditional elearning content, exercises, and quizzes to create a robust online learning experience, hosted on an LMS, so that HR could track usage and follow up where needed.

Examples of Skills-Mapped Curriculum and Courses

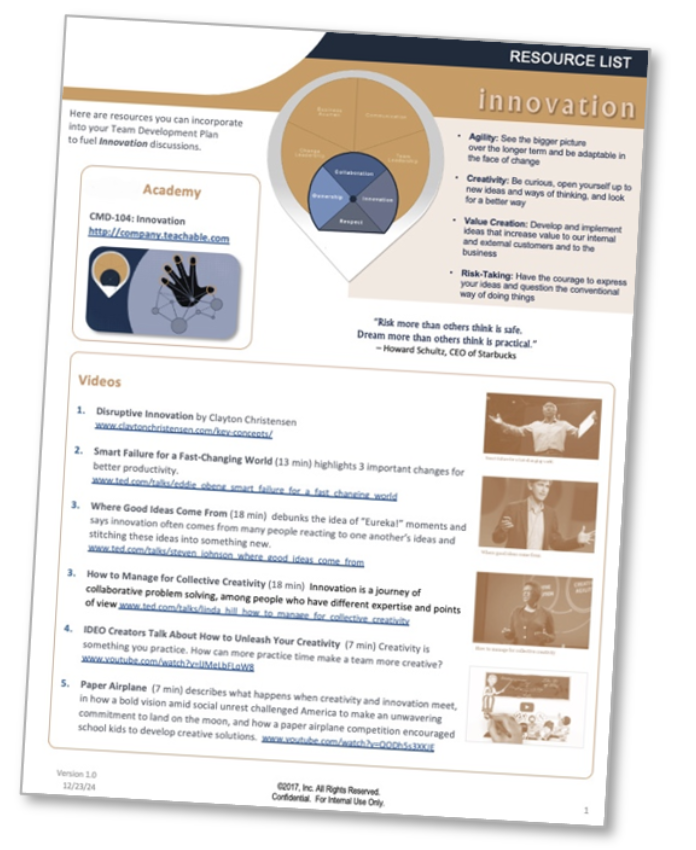

Curated Resources: To encourage pull-through and support managers in having development conversations, we developed a library of curated resources. For each Core Skill, we developed a 2-page interactive PDF with titles, descriptions, and links to curated resources, such as selected courses, videos, books, articles, and other resources intended to help the individual develop that skill. These 2-pagers were made available on a neatly organized SharePoint site, where all the change initiative’s materials were housed for quick access.

Team Development Resources: Curated resources could be used by people leaders, who were asked to have regular conversations with their team and drill down into a particular skill and how the team as a whole could improve that capability.

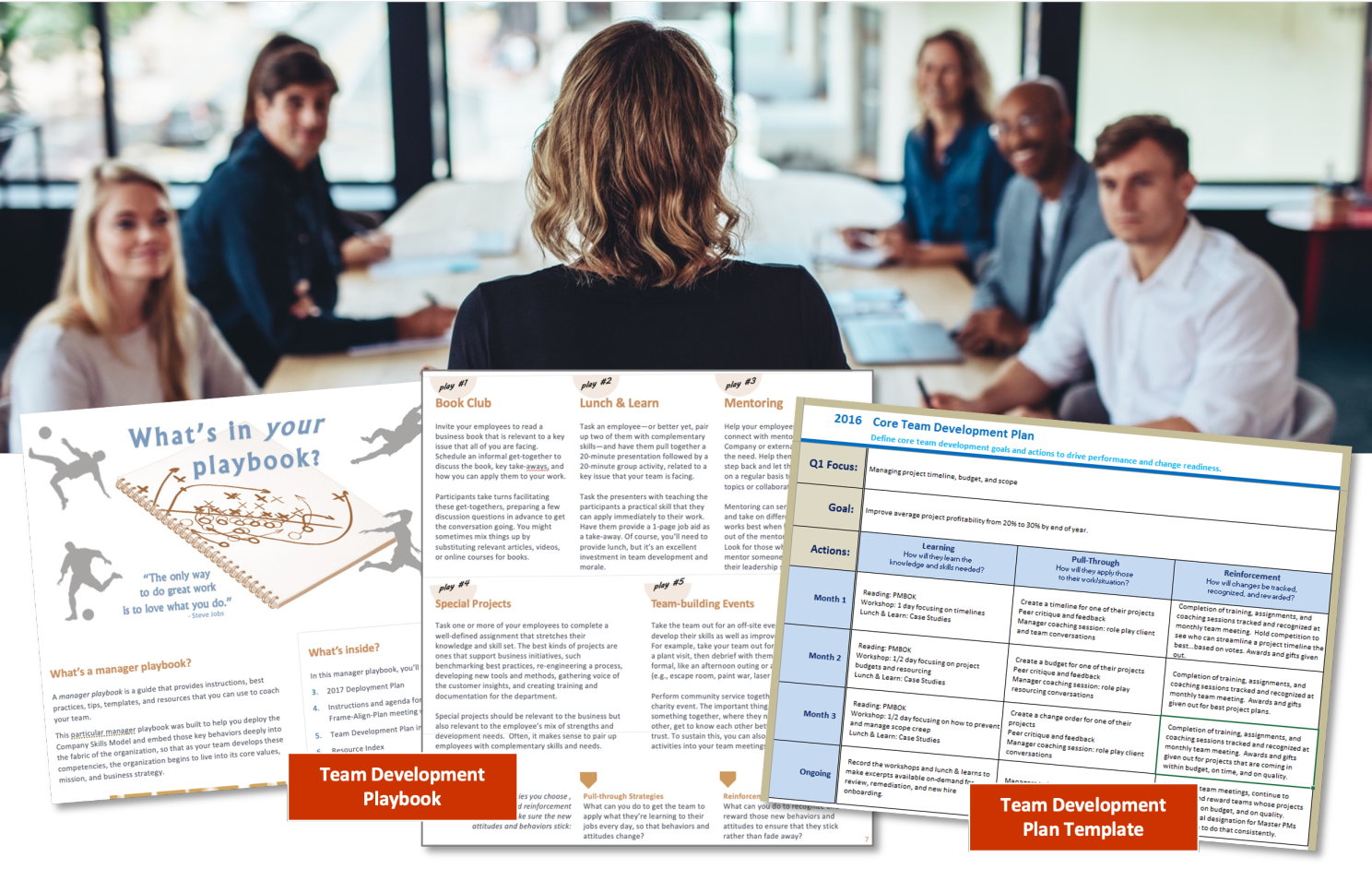

Managers were given a playbook to guide them. It contained strategies, talking points, tips, and structured activities that they could run with their teams to initiate capability discussions and identify specific things that the team could do to improve a particular skill.

People leaders were asked to create and implement their team development plan, using a template and examples provided. They submitted those team plans each quarter.

For example, one quarter, a team might discuss collaboration, how they could better collaborate with each other as well as how they could improve collaboration with other departments. After some discussion, they might identify a few specific changes they would commit to making.

Part 3: Change Ambassadors

While it was important to have a big top-down push from senior leadership to get the whole organization moving on this cultural change initiative, we recognized that a bottom-up push was also needed, so the CHRO enlisted some help.

The CHRO tapped a group of high-potential middle managers to lead the grass-roots change efforts locally for a given population. This diverse group ensured representation across all sites, business units, and global functions. The Change Ambassador is a pivotal role in bringing about widespread change.

Prior to launch, the Change Ambassadors received special training, helping them not only master the skills model and the various resources available but also to develop their influence and change leadership skills.

Driving Local Change Plans: Each ambassador was asked to work with their respective leadership teams to develop and implement local change plans. Their plans might involve staging events, running team-building activities that reinforced the cultural changes, or conducting train-the-manager sessions.

Mentoring Managers: Each ambassador made plans to engage with individual people leaders to mentor them on using the new resources, initiating one-on-one conversations, and engaging their whole team in broader capability discussions. Different managers needed different amounts of support; and where needed, the ambassadors could pull in their HR Business Partners for added help.

Supporting Each Other: Leading change efforts is exhausting, lonely work that can burn out the most ardent evangelists if they don’t have a support system. The Change Ambassadors buddied up with each other to provide mutual support, act as a sounding board, and share ideas. Systemic change is a team sport!

Quarterly Ambassador Touchpoints: After the launch, the CEO and CHRO met with the Change Ambassador team to debrief each quarter—what was working well and what course corrections were needed—and to discuss plans for the next quarter.

Design Principles at Work

This case study illustrates the real-world application of four performance-based instructional design principles:

- Get Senior Leaders Out Front: Ultimately, the most senior leaders in the business have two primary responsibilities: drive the business strategy and foster the right culture to support it. However, senior leaders cannot simply delegate culture change any more than they can dictate it or silently wish it into existence. They must put themselves out there and vigorously evangelize the changes they want to see, which includes modeling those behaviors, reinforcing them, extinguishing the behaviors that run counter to them, and continually talking about those behaviors to keep the conversation alive. To encourage this, we asked executives to get on camera and talk about the values, skills, and behaviors that were needed to succeed, and they came through for us. They also participated heavily in key decisions, spoke at town hall meetings, and attended ambassador touchpoints. They visibly owned the change, so employees did not mistake the desired cultural transformation for a program-of-the-month initiative that would soon fade away.

- Get Concrete: When trying to do something as difficult as convincing thousands of smart people to change the way they work, it’s important to be specific about what those behaviors are, so everyone understands what they are, why those behaviors are needed, and what skills need to be developed. Competency models are typically too broad and abstract to be of any real use. We worked backwards from the leadership team’s vision of what the new way of working should look like, identified key behaviors and the skills supporting those behaviors. Then we embedded those specific skills and behaviors into every aspect of talent acquisition, talent management, performance management, and talent development as well as into the change communication plan and change management efforts.

- Change is a Team Sport: Organizational change initiatives require leadership sponsors to do their part, but more than that, they need the active, widespread support of lower-level leaders—both formal and informal ones—to pull those changes through where the rubber meets the road, or in this case, where the electrical wires meet the circuit board. We engaged high-potential leaders from across different business units and sites to act as change ambassadors, training them and empowering them to be local change agents. In an effort to get teams talking about the new values, behaviors, and skills and implementing team development plans, we engaged people leaders at all levels. This whole systems approach to change respected the local differences while marshaling the grass-roots support needed to make meaningful and sustainable change.

- The Change Must Be a Business Imperative, Not Just an HR Goal: Although we worked closely with the CHRO, his HR Business Partners, and the Training team, we insisted that the global and local business leaders needed to take ownership of the change, the change strategy, and the results. For example, when the Skill Guide was launched, it was rolled out by the business unit leaders, not by HR or Training. The change goals/metrics were added to the MBOs of all business units, not just to the HR department’s list. When Change Ambassadors were needed, the request came from the business unit heads, not from HR. When those Change Ambassadors were trained, some of the business unit heads participated as instructors and guest speakers. When the training was being developed, both senior leaders and business unit leaders participated in recorded interviews that were excerpted and used in the elearning modules. In other words, the faces, voices, and handprints of the local business leaders were all over this change initiative, and it was clear to everyone that this was a business imperative, not an HR or Training initiative.

Much of the architecture for this initiative was put in place within 4 months of kickoff and ran for more than a year until the organization transitioned into a new steady state.

This case study demonstrates how a whole systems approach to organizational change, with a skills framework at the center, can help to bring about rapid, systemic transformation, fundamentally changing the culture around how work gets done.

We welcome your perspective on other ways to make workplace training more effective and impactful. Comment below!